In the midst of the market meltdown in the fall of 2008, we were in the field doing research on behalf of DRI (Defense Research Institute) on the Future of Litigation. Alternative Fee Arrangements (AFAs) were one element of that research. Extensive interviews with general counsel and law firm leaders highlighted three primary motivations behind the search for AFAs:

- Some simply needed to cut costs. Fee arrangements trend toward discounts and blended rates in these contexts.

- Some needed predictability, particularly if they have a block of recurring or continuing litigation. Fee arrangements in this context trend toward fixed caps for matters – or more often for blocks of business.

- Some were driven by risk management models or strategies. In this context fee arrangements trend toward some form of contingency.

Now, that research focused solely on litigation. Further, there has been considerable growth in non-hourly based fee arrangements since that time. For instance, in early 2009 only 29% of law firm leaders believed growth in non-hourly billing was a “permanent trend.” That has grown to 80% in spring 2012 (see Altman Weil’s Law Firms in Transition survey).

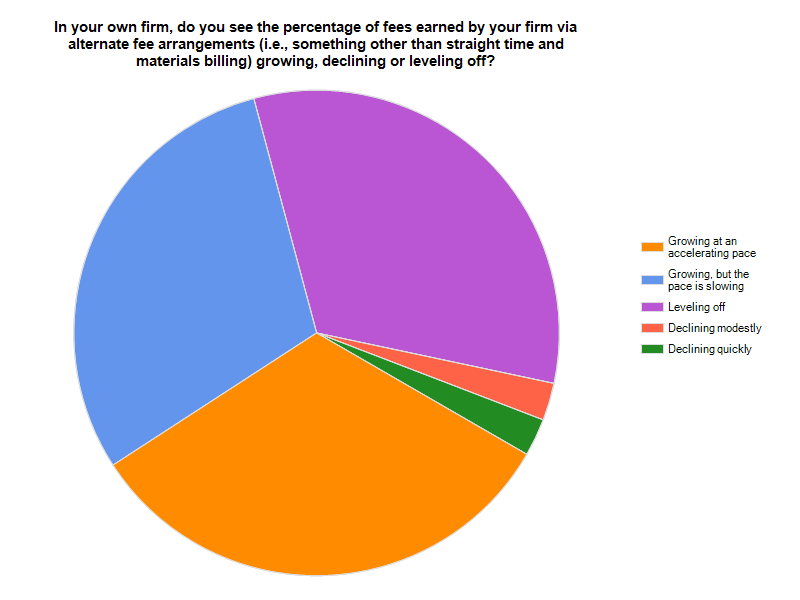

Our law firm strategy question of the month focused on AFAs this month. Roughly, two-thirds of respondents indicated that AFAs are growing (about a third find AFAs continue to grow at an accelerating pace).

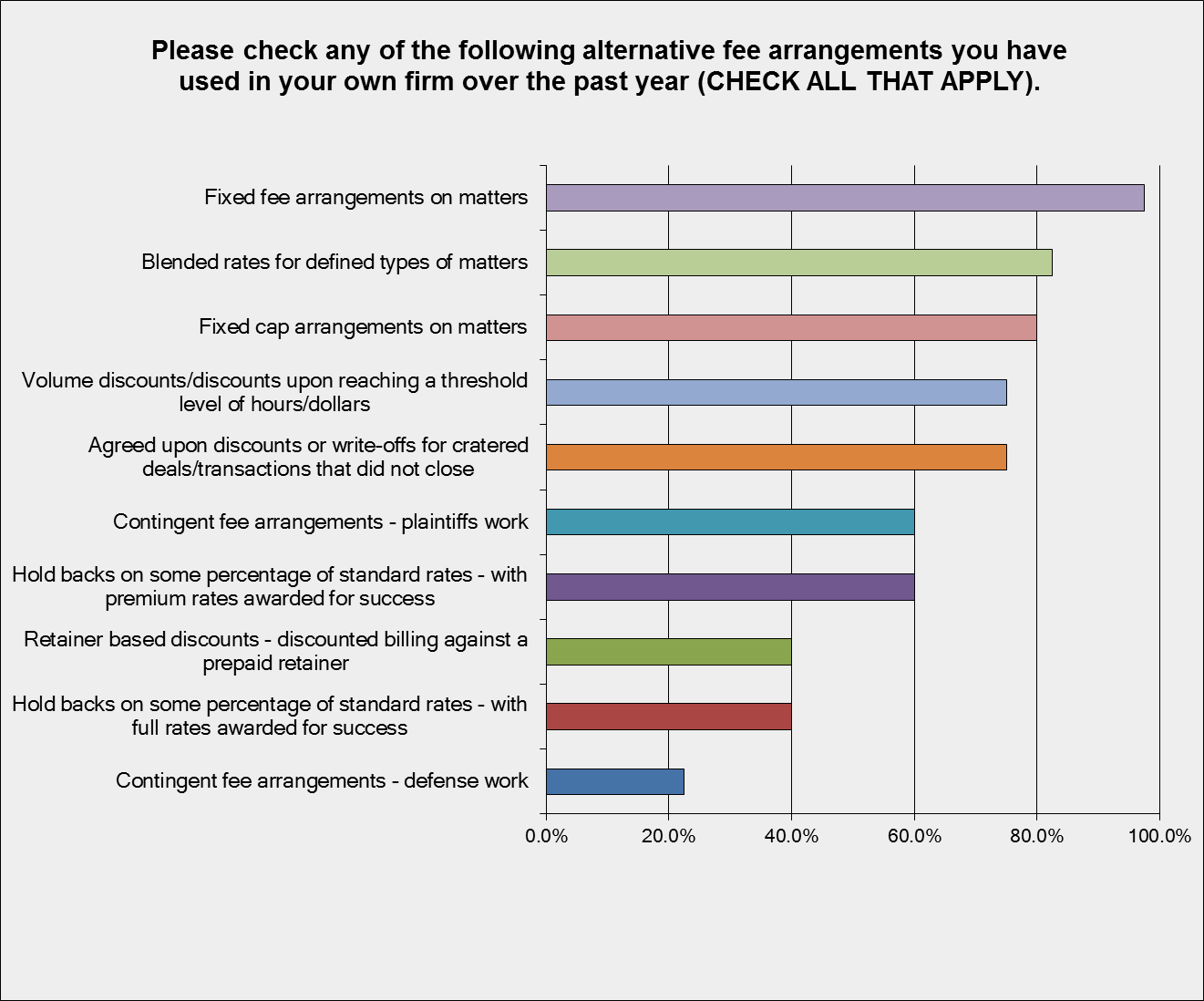

Anecdotally, we have seen many clients ask for AFAs only to revert to a simple discount off standard rates – continuing to rely on hourly billing for a variety of reasons. For purposes of this month’s survey, we did not include discounts as an AFA – focusing instead on non-hourly forms of fee setting. In order of most prevalence, AFAs in use today include the following.

The question also allowed respondents to add other AFAs (not on the list above). Other AFAs in use include collars/monthly retainers; deferred billing arrangements for start-ups awaiting venture funding; and highly customized approaches that provide predictability for clients.

Finally, an open-ended question at the end of the survey invited people to share “unique insights you have gained from the deployment of AFAs.” People were very generous with their insights and the key insights are summarized in the following points.

- Firms have learned the value of well analyzed data – on costs and on the work being subjected to an AFA. For instance, one firm reports very good results on contingency oriented arrangements – in cases where experience informs their understanding of the upside for recovery. Others noted that they have learned to improve the profitability of fixed fee arrangements – by understanding underlying costs and their approach (staffing and work process) to the work.

- Many have found that effective communication with clients and prospective clients is a key to success. That enables the firm to provide the predictability (or other objectives) the client is pursuing. Further, it reinforces the strength of the relationship – clients appreciate the fact that their law firm is listening and responding. Finally, it ensures that when risks are being shared (such as in a contingency arrangement), both the firm and the client are prepared for changing conditions.

- Many also noted that effective AFAs are not easy to construct. They take time to get it right – for the client and the firm. They require attorneys to approach both the client relationship and the legal work differently. And, they end up simply being a margin reduction if time and intellect are not invested in their creation and execution.

- A few people noted that one key to success is doing effective post-mortem reviews of AFAs. As one managing partner noted, “the most difficult part is circling back to see if the arrangement worked…”

Note that firms who have a higher proportion of their fees earned via AFAs were more likely to be experiencing a slow-down in the growth of alternative fee arrangements. Certainly, the move toward non-hourly billing is not a passing phase. Knowing your own cost structure, being able to manage the work consistent with the AFA (either via project management or via staffing models), and being able to learn from each experience are critical to success.

We thank the many law firm leaders who continue to share their insights and experiences via these questions of the month.