This article is a follow-up to a major section in our recent article Non-Lawyers: A Critical Success Factor for the Law Firm of the Future. Namely, when should non-lawyers – and specifically, business development professionals – be expected to interact directly with major clients? This follow-up is both informed and motivated by the comments, feedback, speaking invitations and other conversations that original article sparked.

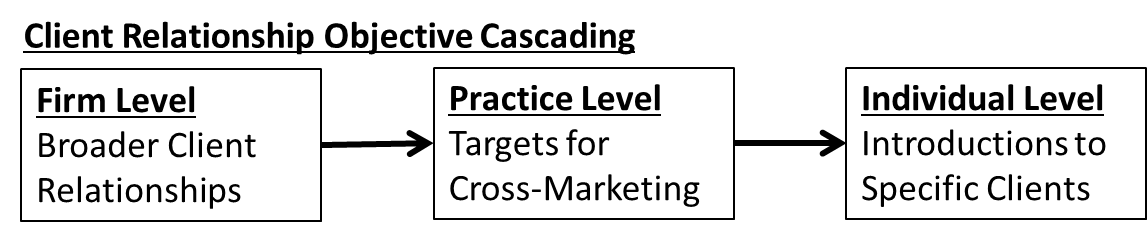

To be clear, we are talking about non-lawyer involvement in communications with major clients. By major clients we mean that group of clients that (with the possible exception of the very largest law firms) fall into an 80:20 or 70:30 rule (i.e., the 20% of clients who represent 70% or 80% of the firm’s revenues). That especially includes clients for whom the firm provides multiple legal services (i.e., clients served by multiple practice groups). Even more particularly, that should include major clients who are using other law firms in areas where your own firm has demonstrated strengths (i.e., where your firm is not getting work from otherwise great clients in areas where your firm has exceptionally strong capabilities).

Are You Advocating Cutting Lawyers Out of the Relationship?

The short answer to that question is, “of course not.” So, let’s stipulate some things that may be obvious, but ought to be underscored nonetheless.

- Lawyers are the primary contact(s) with clients for the delivery of legal services and the management of legal (and often other) risks.

- Nearly 100% of current client relationships originated with a lawyer or team of lawyers – though in many instances, the “originating” attorney is no longer active in the practice of law (i.e., the client relationship pre-dates the current team serving that client).

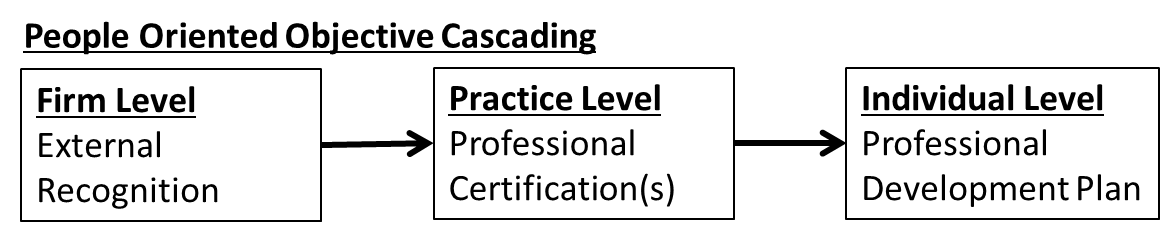

- Lawyers should (in fact must) remain integral to client relationships – maintaining, improving and growing those relationships.

The point is not that lawyers are set to be thrown on the trash heap of history. Rather, the point is that the efforts of client serving attorneys can be greatly enhanced and augmented by involving non-lawyer (particularly business development) professionals in client communications. Also, while a few firms are turning to (non-practicing) lawyers to take on these business development or client relations roles, the majority will be filled by professionals whose training and experience has prepared them to lead business development in a professional services setting.

So, How Can/Should Talented Business Development Professionals Be Interacting With Major Clients?

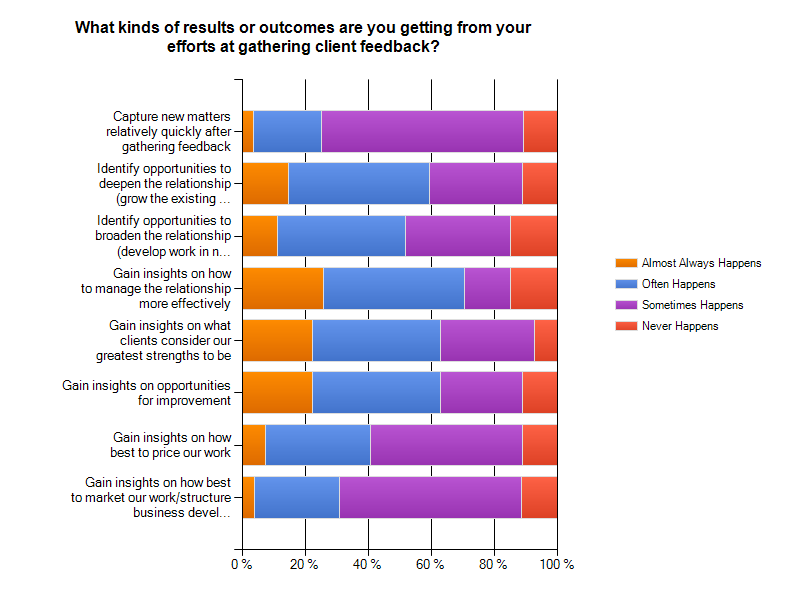

Business development professionals are (or at least should be) extremely well positioned to gather systematic, objective, constructive, deep feedback and input from major clients. That feedback gathering can benefit from the involvement of managing partners, practice or section leaders, or others law firm (i.e., lawyer) leaders. However, law firm leaders are generally too busy to maintain regular, systematic contact with major clients. Gathering that input via well-structured, extended conversations with multiple people within major client organizations is the starting point for non-lawyer interaction with clients.

Remarkably, relatively few firms are gathering feedback from clients (major or otherwise) on a systematic basis. Even in firms that are committed to gathering client feedback informally, many do not leverage the skills and experience of business development professionals to do so. Many firms on the smaller end of what we would consider to be mid-sized may not have a seasoned business development professional capable of leading that process (i.e., the marketing and business development function is staffed by people skilled in marketing communications and/or event planning). In that case, feedback gathering can be outsourced – frankly, the return on investment is outstanding.

With systematic, objective, constructive, deep feedback and input from major clients in hand, what should the firm do? There are several answers to that question.

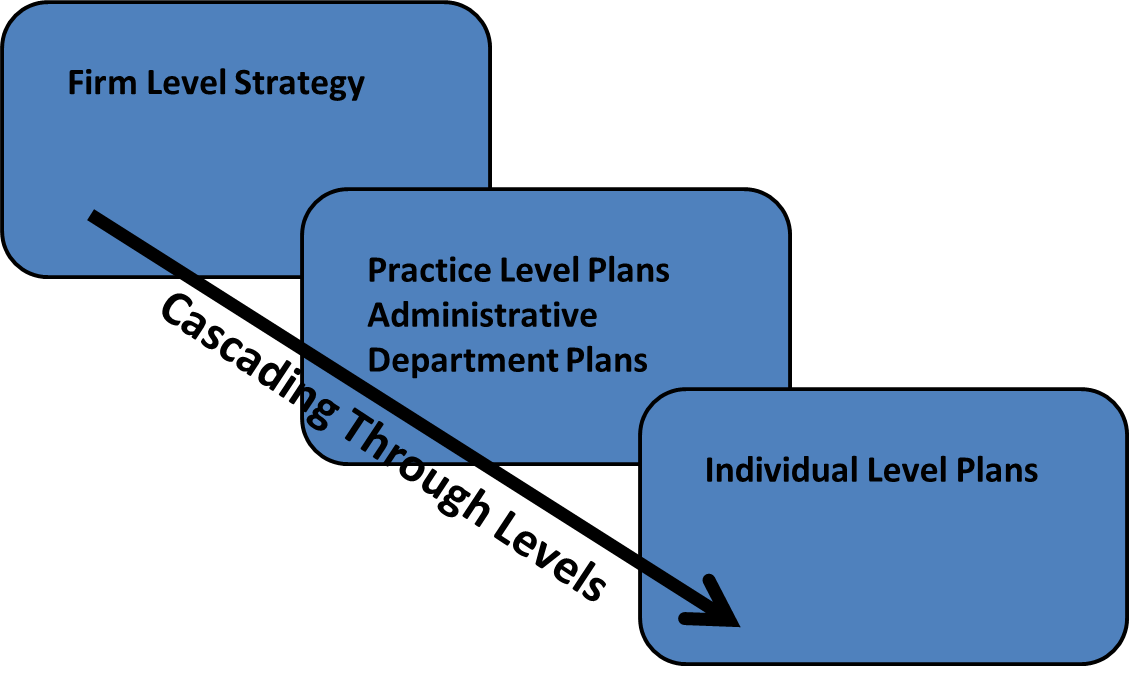

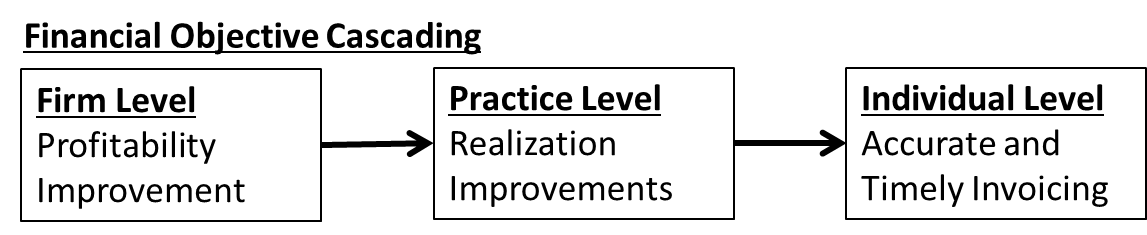

- Most importantly, firms need to use that client input to help the team of lawyers who serve the client on a day-to-day basis – together with lawyers who perhaps should be serving that client – to develop and implement a plan to expand the relationship. Seasoned business development professionals can and should facilitate this process (though it can also be outsourced if necessary).

- That includes both deepening the relationship (i.e., doing more of what the firm is already doing for the client, ideally with a more engaged and informed team) and broadening the relationship (i.e., bringing other strengths of the firm to bear on behalf of the client – providing legal assistance in other areas where firm strengths align well with client needs).

- That also includes tracking and coordinating implementation of those “client service plans” (which almost certainly should include metrics, action plans, and milestones).

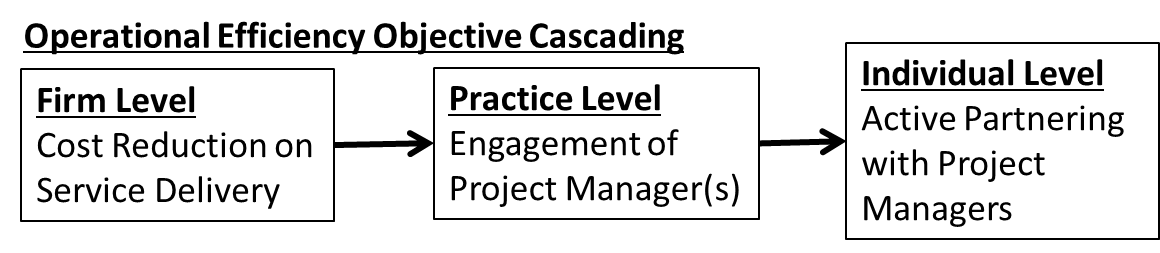

- In addition, that feedback needs to be used to draw other non-lawyers into the client relationship. In the current environment, client feedback often uncovers expectations and/or needs that require the assistance of IT professionals (e.g., extranets, connectivity, proprietary systems, etc.); knowledge management expertise (e.g., process automation, database integration, smart forms, etc.); project management expertise (which may reside at the firm and/or at the client’s organization); and finance expertise (e.g., cost analysis, creative pricing arrangements, etc.). Again, a seasoned business development professional should be able to bring this extended support team to the table and coordinate their efforts with those of the rest of the client service team.

The ultimate vision for non-lawyer interaction with clients ought to be somewhat akin to a more traditional marketing function in a corporate setting. In a corporate setting, market intelligence and customer input is used to drive an integrated marketing function that goes well beyond marketing communications and business development. Some may remember the “Four P’s” from Phillip Kotler’s Introduction to Marketing text books (i.e., Product, Pricing, Promotion and Placement/distribution). Gradually, the legal industry is moving toward this model. For instance, there are reportedly over 300 “pricing directors” at law firms now. Similarly, there are more and more non-lawyer business development and outright sales roles.

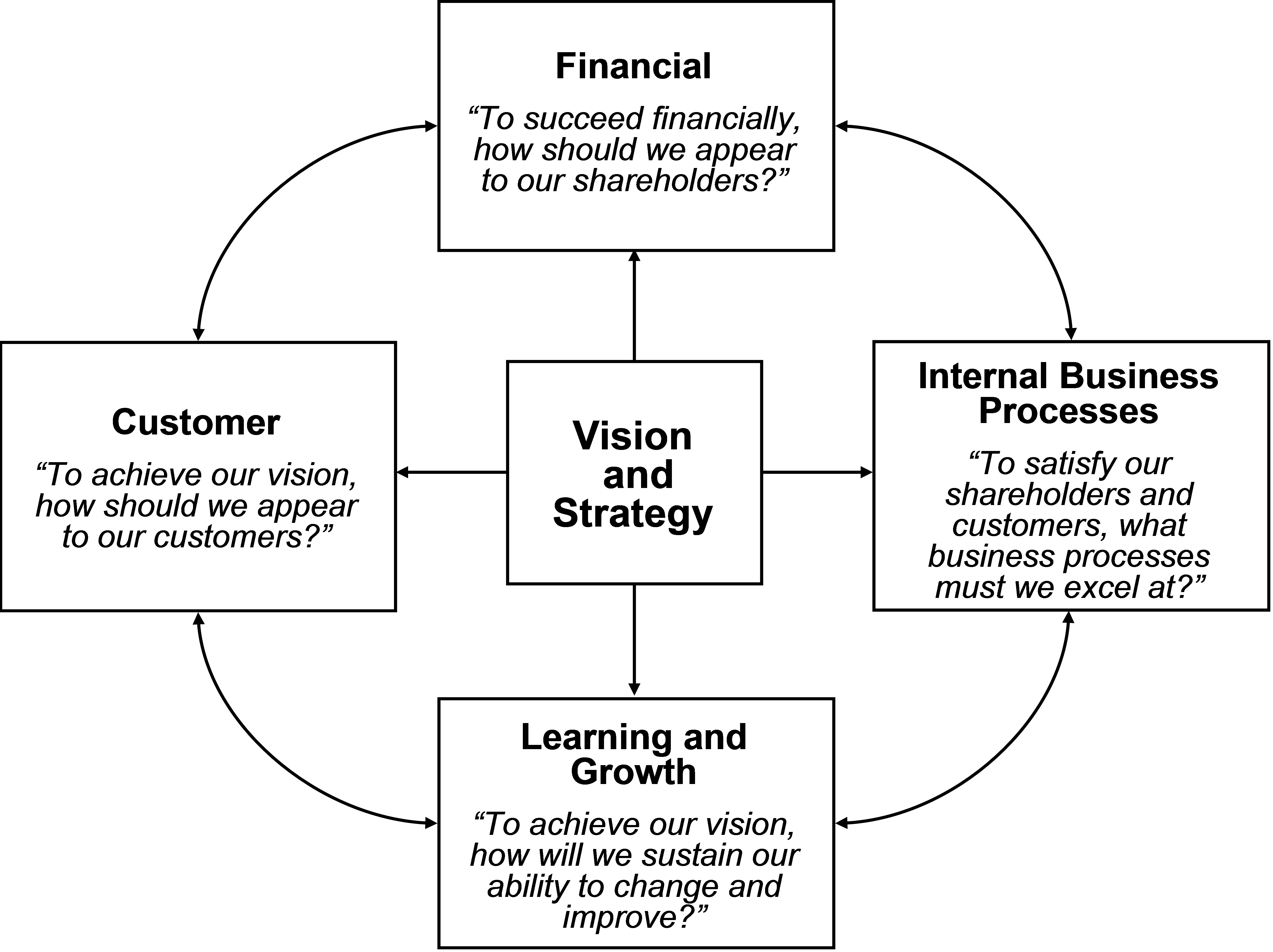

Ultimately, these roles need to be integrated and coordinated. Call the leader of that group the Chief Marketing Officer, the Head of Client Relations, or some other title. Frankly, the title is less important than the function, which is to bring the outside into the firm (e.g., client input, market intelligence, competitor intelligence, etc.) and to coordinate the firm’s response to that information in ways that (profitably) extend and deepen existing client relationships and establish new ones.