One of the key findings of our April 2012 “strategy question of the month” involved the strategic importance practice groups (and filling out the practice group portfolio) have in determining law firms’ merger and acquisition strategies. In the write-up of those survey findings, we promised to pull out and abridge a section of John Sterling’s book Strategic Planning for Law Firms: A Practical Roadmap. The book includes a lengthy chapter explaining the background and the application of several proven strategic management tools and models – including applying portfolio management tools to practice groups. What follows is an excerpt from the book addressing the portfolio management concept.

* * * * * * * *

Portfolio analysis (and portfolio management) traces its origins to the leading management consulting firms of the 1960’s and early 70’s. There were several variations on the same underlying idea. Namely, that the key to effectively managing a business with multiple product lines and/or multiple divisions was to understand the role each should play in the company’s overall strategy.

Further, each approach to portfolio analysis examined products or business units from two fundamental perspectives. First, they looked at the relative competitive position of the business or product line. Second, they assessed the market in which that business unit or product competed.

Law Firm Application

The application to law firms – particularly general practice business law firms – should be quite apparent. As law firms have grown, developed multiple practice and industry specialties, and become more managerially complex, the need to apply some order to that increased complexity has grown. Portfolio analysis and portfolio management provide a set of tools well designed for precisely this type of organizational complexity.

Essentially, practice groups (generally including industry groups) are in most respects like a strategic business unit in a diversified corporation. They offer distinct services, have unique underlying “production” or operational capabilities, face identifiable competitors, and compete in markets that differ (sometimes dramatically, sometimes subtly) from the markets of other practices. Further, it is entirely possible (in fact advisable) to measure the financial performance of a practice group – if not on a fully loaded profit and loss basis, then certainly on the basis of contribution to firm profits (e.g., revenues net of direct expenses before the allocation of firm overhead).

Further, given the inherent limitations on resources, it is not feasible to treat every practice the same. Nor is it sensible to expect the same results and contributions from every practice. Some practices are well suited to attract new clients to the law firm. Some are well positioned to drive profitable revenues. Some are integral to maintaining a deep and lasting relationship with clients. Ideally, a firm should be able to define its expectations of each practice based on a portfolio analysis – and the practices should be able to pursue a valuable role within the firm in response to those expectations.

Using and Applying the Tool in a Law Firm Setting

Portfolio management is a straightforward process in which management (or a strategic planning committee) ranks practice along two critical dimensions. The attractiveness of the market in which the practice group competes; and the relative market position/strength of the practice group. Each of these dimensions is discussed in more detail below.

Market Attractiveness

The attractiveness of any given market is a function of a variety of factors – some purely objective, others more subjective. The key to using the portfolio analysis tool is to agree on a consistent set of “attractiveness factors” and each factor’s relative importance.

Some examples of market attractiveness factors follow.

- Competitive intensity influences the attractiveness of a market. Highly competitive markets may not be as attractive as those with less competition. Note that a separate tool designed for assessing competitive intensity is discussed in some depth in a subsequent chapter.

- Rate sensitivity is an issue in many legal market segments. Markets or specialties that do or can bear premium billing are clearly more attractive than those with a high degree of rate sensitivity.

- Market growth is another obvious factor in rating the attractiveness of markets. Patent litigation was attractive throughout the 1990’s and 2000’s in large part because of the consistent growth in that market.

- Market size must also be considered. A large market is generally more attractive than a small one. A large, growing market is even better.

- The needs and demands of the firm’s existing client base is usually a factor. For instance, if virtually all of the firm’s corporate clients need and use the firm’s tax services, the tax market would be rated favorably on this particular factor.

Other factors might also be included in this analysis such as historical or future profitability; regulatory and other external influences on the market; and the technology required (now and in the future) to compete effectively in the market.

Relative Market Position/Strength

The other dimension to consider in a portfolio analysis is the relative market position of each practice group. The key word is relative – to key competitors and to the needs and expectations of the market.

Again, a variety of factors determine the relative market position of a practice. Some examples follow.

- The relative quality of lawyers and/or work produced is a key factor, but is often difficult to rate objectively. Third party ratings can serve as a proxy here (e.g., number of attorneys listed in Leading Lawyers or tier ranking in Chambers).

- Practice profitability (measured by contribution, realization, revenue per lawyer, net income per partner, or other means) can be an indication of relative market strength. As noted above, profit potential can also serve well as a factor in determining market attractiveness.

- Market reputation/perception can be a strong indication of a practice’s relative strength. Is the practice considered the leader, among the leaders, at parity with most firms, lagging other firms, et cetera?

- Market share – locally, regionally, or nationally – is another key measure of relative market strength. Unfortunately, law firms generally have to rely on the number of lawyers they have in a given area as a surrogate for market share. Nevertheless, share and share growth are good measures of relative market position.

Plotting the Portfolio

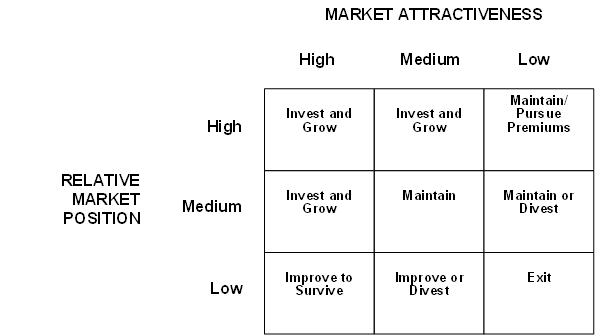

Assessments of each practice group’s relative market position and the attractiveness of the practices’ respective markets can be viewed graphically by juxtaposing the two dimensions (market position and attractiveness) on a matrix. At a basic level, market attractiveness and relative market position ratings can be broken down to three “generic grades” – high, medium, and low.

The result is a three by three matrix like the one pictured below.

The matrix suggests relatively generic strategies. Naturally, the specific strategies a firm should pursue depend on many factors, some of which reach well beyond the scope of this analysis. Nevertheless, portfolio management is an extremely valuable tool in making resource allocation decisions among practices.

* * * * * * * *

There is considerably more discussion of both the generic strategies and a “how to” on applying the portfolio management tool in a real world setting in the book. And, we are happy to discuss the tool with you directly over the phone (312) 543-6616 or in the comments section below.